Actor Model - Introduction

Source code for this article can be found on Github.

The actor model has been around since 1973, and was created to ease the development of big asynchronous systems, which didn’t exist at that time1. Actors decouple software entities even further than objects can do in OOP2 systems. Actors are a good way to solve concurrency problems like the ones we discussed in the previous article. Let’s first see how the actor model works.

The actor model

A software application implementing the actor system will have actors as logical entities. Actors are software entities with the following properties:

- Actors run inside their own thread3.

- Actors encapsulate their own state.

- Actors logic isn’t called directly by other software entities (actors or objects), but is requested via messages.

- Actors can create child actors. The parent actors describe strategies for handling failures in child actors.

Implementations of the actor system often provide the top level actor and child actors can be added programmatically. This hierarchy works very much like an economical organization, just as actors work very much like the employees of the organization. Whenever an actor has too much functionality to manage, it can start some child actors to delegate sub tasks to. When the task for the child actors is still too big, additional child actors should be created to delegate work to.

The delegation of tasks (by software engineers) continuous until tasks are small enough to handle in a synchronous context. Actors that run these tasks are often called workers and actors delegating work are called supervisors.

Consider a group of people having to finish a report in a Dropbox stored Word document. They first all work inside the same document: it quickly becomes a mess. It’s unclear which version should be merge with what version of their peers. This group now chooses a leader (supervisor) who is responsible for delegating chapters and merging the final result.

Because each actor runs in its own thread (or via a scheduled timeslot3), jobs that get delegated to children are automatically run in parallel. Multithreading is actually the key features of the actor based system. The other features of the actor (mainly) make managing this multithreading approach possible.

By encapsulating its own state which may only be accessed by the actors single thread,

Atomic objects and the use of locking are not needed.

Communication between actors can’t happen with method calls (or at least shouldn’t). Whenever a method is called it enters the call stack, and would thus be blocking. Instead actors send messages to each other. These messages are send in a fire-and-forget fashion. If a return value is suspected, the recipient of that message should send a message back containing that return value.

Actors shouldn’t be concerned with business logic inside a child, they just expect a return message when they request something (if needed). To leverage the full advantages of the actor system the developer should take care only to send immutable data between actors. When implemented properly: actors are greatly decoupled.

Coming back to the economical organization, consider a manager that knows nothing of programming being responsible for a software release. This manager is great in delegating and managing tasks to its subordinates but he doesn’t have to know about the fine details of programming. This is just like the supervisors and workers in the actor model.

try/catch clauses are not helpful when working across threads4. As we’ll see in the next article supervisors are also responsible for handling failures of their children.

Practical example

Let’s try to solve our weather problem by the use of actors. In this example we will work with Java again. To use actors in Java we can use the libraries provided by Akka5.

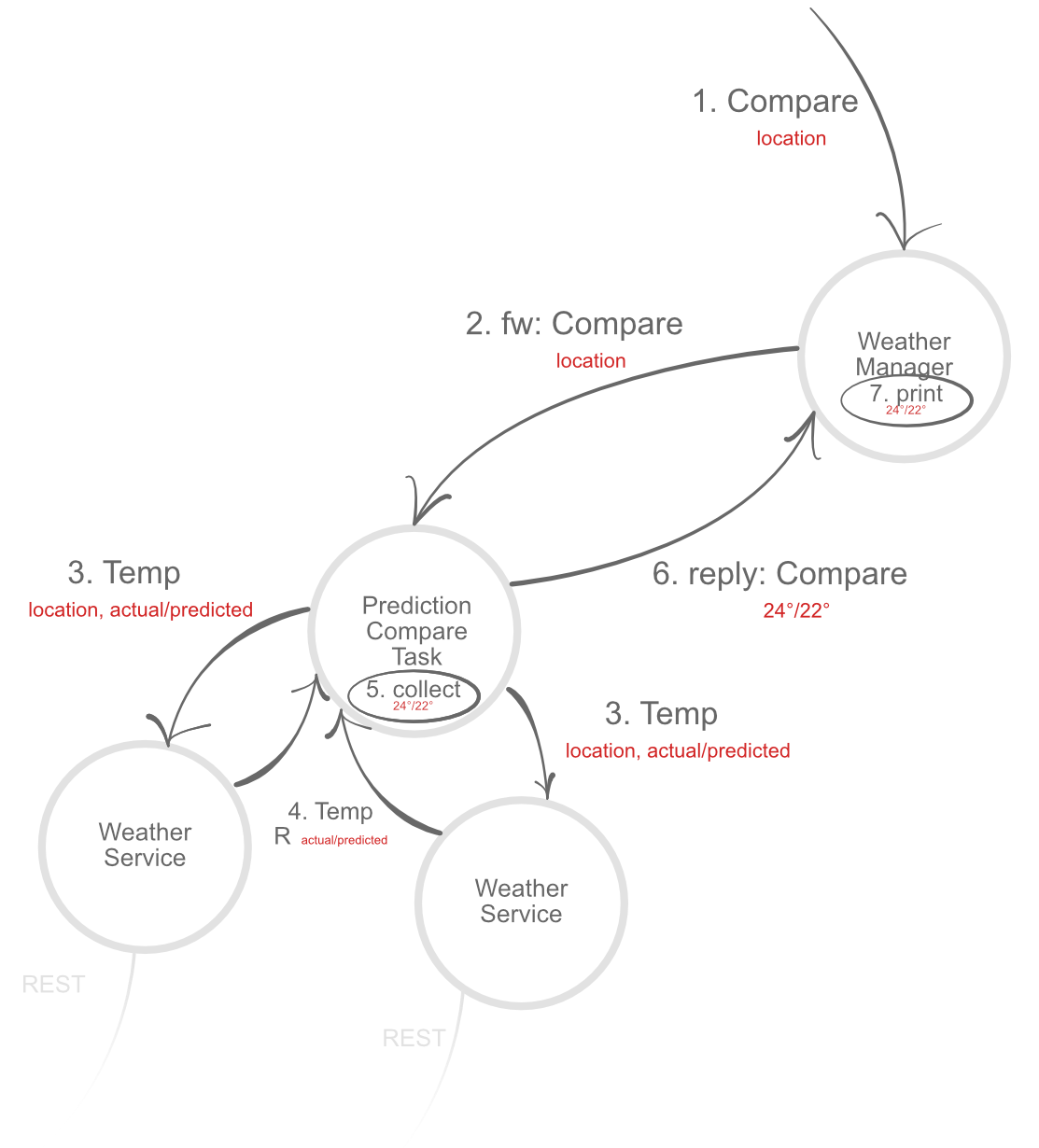

Our actor diagram will look like this:

Let’s walk over each of the steps:

- An external source sends a request to the

WeatherManager.WeatherManageris responsible for printing the result. Because it’s our top level actor it can’t send messages upwards to its caller. - The

WeatherManagerwill create a child actor calledPredictionCompareTask. This actor is responsible for the task of fetching the actual and predicted temperature. In an actor system tasks are often prescribed their own actor, these tasks can therefore run in parallel. - We want to execute fetching the actual and predicted temperature in parallel,

this means that the

PredictionCompareTaskwill create two child actors of typeWeatherService. These child actors are of the same type and can either request the predicted or actual temperature. - When the

WeatherServicehas finished collecting data it returns that data to its caller, after which it will destroy itself, cleaning up its resources. - The

PredictionCompareTaskcollects the information it received and returns it once both children send their data successfully. - The result of the request is send back to the manager after which the

PredictionCompareTaskactor destroys itself. - The

WeatherManagerprints the result to the console.

Implementation

First we create the ActorSystem:

ActorSystem system = ActorSystem.create("weather");

A Java application can have any number of actor systems running in the JVM but only having one logic tree is recommended. We will now add actors to the actor system in an hierarchical order. We start with a management layer which will manage the fetching of weather data.

class WeatherManager extends AbstractActor {

private final LoggingAdapter log // <-- 1

= Logging.getLogger(getContext().getSystem(), this);

static Props props() { // <-- 2

return Props.create(WeatherManager.class);

}

private void comparePrediction(ComparePredictionRequest r) { // <-- 5

log.info("requestId: {} received, requesting prediction for {}"

, r.requestId, r.location);

}

@Override

public Receive createReceive() {

return receiveBuilder() // <-- 4

.match(ComparePredictionRequest.class,

this::comparePrediction)

.build();

}

static final class ComparePredictionRequest { // <-- 3

final long requestId;

final String location;

ComparePredictionRequest(long requestId, String location) {

this.requestId = requestId;

this.location = location;

}

}

}

This is the code we need for the WeatherManager for now. By extending akka.actor.AbstractActor,

this object can be used as an actor in the Akka system (that we created in the Main class).

Let’s look at some common building blocks the actor exists of:

- Akka provides its own logging adapter. It logs messages to the console (non-blocking) and logs the actor address in the system, which might be useful for debugging purposes. We will discus the actor addresses later.

- Actors aren’t created with the

newkeyword, instead they are created by theProps.create(). The props factory function is something often used with Akka actors. - The inner class

ComparePredictionRequestforms the definition of a message then is send to this actor (but may also be send between other actors). In most cases messages include arequestIdwhich is used by the sending party to match responded messages. Here we also provide the location for which we want to receive the predicted and actual weather. - The receive builder is the only abstract method of

AbstractActor, which means that we must overwrite it. TheReceiveobject that’s returned will contain the logic for handling messages. If we want an emptyReceiveobject we would write the following snippet: returnreceiveBuilder().build();Thematch()function makes that whenever the actor receives aComparePredictionRequestit will delegate it to thecomparePrediction()function. - In this function we will handle the message, for now it just outputs the request parameters, but we’ll fix this soon.

Now to create this actor and tell it to do its job we write the following code in the main() function:

ActorSystem system = ActorSystem.create("weather");

ActorRef weatherManager = system.actorOf(WeatherManager.props(), "weather-manager");

weatherManager.tell(new WeatherManager.ComparePredictionRequest(0L, "Eindhoven"),

ActorRef.noSender());

We first create the WeatherManager actor using the factory function we saw earlier.

Now notice that the ActorRef it returns is a reference to the actor.

This reference is special in that Akka will automatically replace it when the actor is replaced

(mainly when a new instance is restarted on failure).

We call the tell() function to send a message to the actor. When run we receive the following output:

[INFO] [09/19/2017 09:58:44.080] [weather-akka.actor.default-dispatcher-3]

[akka://weather/user/weather-manager] requestId: 0: Requested weather prediction for Eindhoven.

Because the WeatherManager runs in its own thread, the app never stalls.

The thread (scheduled timeslot) it’s run on can be seen in the logs (dispatcher-3).

We can also see the address of the actor that prints the message (akka://weather/user/weather-manager).

When connecting actors via http (provided by Akka),

we can even send messages to actors

between JVM’s via the akka protocol.

One problem we face is that messages can only be send between actors,

meaning that we cannot receive replies from our Main class.

When we send the ComparePredictionRequest from our Main class we didn’t provide a sending actor (Actor.noRef())

so we can’t receive any responses in our Main class due to the lack of a mailbox.

This means that the response message should be send via a (blocking) method call to the main class.

These situations, where multiple threads must run the same code, should be avoided at all cost.

This is exactly why we designed the WeatherManager to finish handling this message (by printing its return value).

Let’s continue our example by creating the actor that will run the tasks.

Our task of fetching the predicted and actual weather will be executed by the children of the PredictionCompareTask actor.

public class PredictionCompareTask extends AbstractActor {

private final LoggingAdapter log =

Logging.getLogger(getContext().getSystem(), this);

private String location;

private ActorRef sender;

public PredictionCompareTask(String location) {

this.location = location;

}

private void compareRequest(ComparePredictionRequest r) {

sender = getSender();

log.info("Received request: {}. I'm supposed to get the {} temperature."

, r.requestId, location);

}

static Props props(String location) {

return Props.create(PredictionCompareTask.class, location);

}

@Override

public Receive createReceive() {

return receiveBuilder()

.match(ComparePredictionRequest.class, this::compareRequest)

.build();

}

}

This actor will be responsible for handling one task of comparing temperatures.

In this case the location is central for the task and thus provided when creating the actor with the factory function.

Props.create() will automatically call its constructor.

The message received by this actor is the same as that of the WeatherManager.

This actor only exists as a means for the WeatherManager to delegate its task to,

this means that these tasks run in parallel (in the runtime of the child actors).

Creating actors that represent just a task is perfectly reasonable in an actor system.

In the WeatherManager class we create a PredictionCompareTask every time we receive a request,

let’s rewrite the comparePrediction() function:

private private Map<Long, ActorRef> actorLookup = new HashMap<>(); // <- 1

private void comparePrediction(ComparePredictionRequest r) {

log.info("forwarding predictionRequest to child: task {}", r.requestId);

ActorRef task = getContext() // <- 2

.actorOf(PredictionCompareTask.props(r.location), "task-" + r.requestId);

actorLookup.put(r.requestId, task);

task.tell(r, getSelf());

}

- We keep track of currently open tasks in the

WeatherManager. - We create a new actor by calling

getContext().actorOf(). getContext()is a function that is inherited fromAbstractActorand its information is used to create an actor that is a child of the current (WeatherManager) actor. The second argument is the name of actors as visible in its location address.

When we run this code we see the following console output:

[INFO] [09/21/2017 13:25:30.630] [weather-akka.actor.default-dispatcher-3] [akka://weather/user/weather-manager] forwarding predictionRequest to child: task 0

[INFO] [09/21/2017 13:25:30.633] [weather-akka.actor.default-dispatcher-4] [akka://weather/user/weather-manager/task-0] Received request: 0. I'm supposed to get the Eindhoven temperature.

All is in order and we can start implementing the WeatherService.

The WeatherService will be an actor that calls the REST API and returns the result.

The WeatherService can fetch both the predicted and actual temperatures.

In our example we will create two instances of the WeatherService in the PredictionCompareTask

and send different messages to each, resulting in the services to perform the right task.

Let’s code the WeatherService:

public class WeatherService extends AbstractActor {

private final LoggingAdapter log =

Logging.getLogger(getContext().getSystem(), this);

private double maxTemp = 30.0;

private long maxLatency = 3000;

/**

* Fake implementation that will fake a request.

*/

private void fetchWeather(FetchTemperatureRequest r) {

double latency = Math.random() * maxLatency; // <- 1

double temperature = Math.random() * maxTemp; // <- 1

log.info("request {}, started fetching {} temperature", r.requestId, r.location);

getContext().getSystem().scheduler().scheduleOnce( // <- 2

FiniteDuration.create((long) latency, TimeUnit.MILLISECONDS),

getSender(),

new FetchTemperatureResponse(r.requestId, r.location, r.type, temperature),

getContext().dispatcher(),

getSelf()

);

getContext().stop(getSelf()); // <- 3

}

… omitted createReceive(), props() and local message classes

}

Some code is omitted for readability. In this example we won’t fetch any real data, but we simulate it,

Akka throws errors when using Thread.sleep() so instead we use the Scheduler .

When we have “fetched” the temperature we will return it to the sender.

- We create a random temperature to send back. The scheduler sends the messages within 3 seconds thanks to the random latency.

- We schedule a message to be send in Akka. We provide the arguments in order: the time frame after which it should send the message, the recipient of the message, the message, a dispatcher that will send the message, the sender.

- After we scheduled the message we can consider the work of the actor done. It can now be destroyed.

Let’s add the final pieces together in the PredictionCompareTask actor to get this app running.

First we need to create the WeatherService child actors and request them to perform work using messages:

private void compareRequest(ComparePredictionRequest r) {

sender = getSender();

log.info("Received request: {}. I'm supposed to get the {} temperature."

, r.requestId, location);

ActorRef actualFetcher = getContext().actorOf(WeatherService.props()

, "fetch-actual"); // <- 1

ActorRef predictedFetcher = getContext().actorOf(WeatherService.props()

, "fetch-predicted"); // <- 1

actualFetcher.tell(new FetchTemperatureRequest( // <- 2

r.requestId, r.location, "actual"), getSelf());

predictedFetcher.tell(new FetchTemperatureRequest( // <- 2

r.requestId, r.location, "predicted"), getSelf());

}

- Notice that we don’t have to provide unique names for each actor, the reason behind this is that only the path should be unique. The path of this actor will include the request ID of its supervisor and thus will be unique.

- We send requests to the child actors to fetch the weather.

Notice this time we don’t register the ActorRef references.

We can count on the child actors to shut themselves down after they finished working.

Besides we know that we want to receive exactly two answers, so on each incoming response

we simply check if our local response has two temperatures in it and respond if it does.

The code above puts the WeatherService actors to work, but it doesn’t handle the responses. Let’s implement:

private Map<String, Double> results = new HashMap<>(); // <- 1

private void handleResponse(FetchTemperatureResponse r) {

log.info("Received response of the {} temperature: {} degrees"

, r.type, r.temperature);

results.put(r.type, r.temperature);

checkFinished(r.requestId);

}

private void checkFinished(long requestId) {

if (results.size() < 1) {

return;

}

sender.tell(new ComparePredictionResponse(requestId, location, results), getSelf());

getContext().stop(self());

}

Whenever a message is received, checkFinished() checks if all its sub tasks are performed,

when this is the case it will send the results back to its parent and kill itself.

The last step is to actually handle the response from the PredictionCompareTask in the WeatherManager:

private void handleResponse(ComparePredictionResponse r) {

log.info("Finished request {} :: temp in {} were predicted as {} and was {}"

, r.requestId, r.location, r.report.get("predicted"), r.report.get("actual"));

}

When we run this program we receive the following logs:

... forwarding predictionRequest to child: task 0

... Received request: 0. I'm supposed to get the Eindhoven temperature.

... request 0, started fetching actual temperature

... request 0, started fetching predicted temperature

... Received response of the actual temperature: 23.445820165556096 degrees

... Received response of the predicted temperature: 24.308724433245 degrees

... Finished request 0 :: temp in Eindhoven were predicted as 24.308724433245 and was 23.445820165556096

We can send multiple messages to the WeatherManager instance and we’ll see that each ComparePredictionRequest

is also processed in parallel. The big advantage of using the actor system here is that,

although we didn’t really had to think about concurrency, we created a system that parallels a couple of sub tasks.

Running our task 100 times will finish in exactly the same time as running it once

(given that our system has enough threads/processing power),

that’s a 100x speed increase when compared to a truly synchronous system.

Conclusion

Coding with actors isn’t all that different than coding regular objects (in OOP programming), thus not a big step to take for developers. By allowing software entities to run in their own threads, it becomes easy to run multiple processes in parallel. Because each actor (should) handles data mutation only on its own data fields (synchronously) you never have to concern yourself with locking or using Atomic variables. In order to achieve the best results the developer will have to make sure he doesn’t send mutable values between actors. Also because all actors run their code synchronously the developer should be aware that supervisors shouldn’t be used for heavy lifting, when they: do they create bottlenecks.

In the next article we’ll look at another feature of the actor system: which is the “supervision strategy”. Using the supervision strategy errors can be handled on the right level, and retry attempts can, for example, be started programmatically.

-

Often using a thread per actor isn’t efficient, this is why schedulers are used. The abstraction is the same in both situations. ↩ ↩2

-

Stack traces print references to code points that wait for a function to wait. We try to minimize these waiting points in the actor model and thus we can’t use the stacktrace. ↩

About the author

My name is Thomas Kleinendorst. I'm currently doing my internship at Bottomline where I'm investigating Reactive technologies and how they fit in their new architecture.