Actor Model - Supervision

Source code for this article can be found on Github.

In this article we’ll discuss the supervision strategy concept. We’ll discover the different kinds of supervision strategies and how they make your actors more fault resilient.

The problem

In traditional object oriented programming we write try/catch blocks when we foresee something going wrong, like accessing a database (that might be down). Let’s look at our synchronous weather example again to see how we handle errors.

In Java, a hierarchical approach can be taken to error handling. Whenever handling the business logic of an error fits into the current class, you handle it with a try/catch block, and when it doesn’t you throw it to it’s caller. Let’s see how this works in practice:

private double callRestForTemp(String location, long timeout)

throws TimeoutException {

long waitingTime = (long) (Math.random() * 6000);

try {

Thread.sleep(waitingTime);

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

System.out.println(

"Called when Thread operation is interrupted.");

}

if(waitingTime > timeout) {

throw new TimeoutException("Timed out!");

} else {

return Math.random() * 30; // <- temp

}

}

This shows the fake implementation for the REST API call.

First we create a random duration that the thread must wait between 0 and 6000.

Then we actually wait that time and check if the waiting time was longer than the actual timeout.

If it waited longer than the timeout we throw an error (java.util.concurrent.TimeoutException)

otherwise return a random temperature.

Methods that can throw an error, and don’t handle the error themselves,

include the exceptions it can throw in the call signature.

The throws TimeoutException on the first line indicates to callers of this method should implement

the error handling themselves or should escalate it upwards.

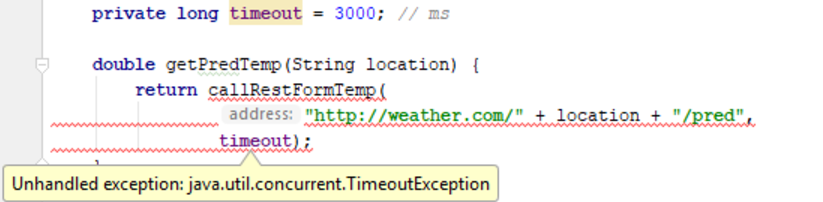

The getPredTemp() function doesn’t implement a try/catch block around the callRestForTemp()

call and also doesn’t escalate it to its caller by including the TimeoutException in its method signature.

To fix this error we change:

double getPredTemp(String location) {

try {

return callRestForTemp(

"http://weather.com/" + location + "/pred/",

timeout

);

} catch (TimeoutException e) {

return 0;

}

}

This doesn’t make much sense,

the caller of getPredTemp might think the predicted temperature was 0 °C when our REST API call fails.

In this case escalating the error is a better solution:

double getPredTemp(String location) throws TimeoutException {

return callRestForTemp(

"http://weather.com/" + location + "/pred/",

timeout

);

}

And catching it in the main() method:

try {

double temp = ws.getPredTemp(location);

} catch (TimeoutException e) {

System.out.println("Weather service unavailable.");

}

To summarize: thrown errors can be handled at the current level or be escalated to handle higher in the call stack.

Now the problem with this approach in the actor system is named in the last sentence: “escalated to handle higher in the call stack”. Tasks that are delegated to an actor are requested in a fire and forget fashion. The actor that receives the message doesn’t run in the same thread and has its own call stack. When something nasty happens in this call stack, there is no way to escalate this error to its caller.

try/catchblocks should only be used for situations where something really goes wrong. Don’t use this construct for “normal” control flow.

Supervision

In actor systems, try/catch blocks are rarely written and considered bad practice in most cases1. The preferred method is to fail the actor entirely and let its parent decide what to do next. Each actor defines a so called “supervision strategy” which is configuration that tells the actor how to handle failing children. Let’s look how this is configured:

@Override

public SupervisorStrategy supervisorStrategy() { // <- 1

return new OneForOneStrategy( // <- 2

10, // <- 3

Duration.create(1, TimeUnit.MINUTES), // <- 4

DeciderBuilder

.match(TimeoutException.class, e ->

restart()) // <- 6

.matchAny(o -> escalate()) // <- 7

.build()); // <- 5

}

There is a lot going, let’s break it up:

- The

supervisorStrategy()is a function existing on theAbstractActorand is overwritten. It expects aSupervisorStrategywhich is a configuration object that tells this actor how it should handle failing children. - The

supervisorStrategy()is a factory function, there are two classes we might return that extendSupervisorStrategy:OneForOneStrategyandAllForOneStrategy. We’ll cover these in a minute. - Whenever a restart strategy is selected, the failing actor will be restarted on failing. If it keeps failing, it will be retried for the number of times defined here. After the max limit was reached the actor will be stopped.

- The restart attempts mentioned in point 3 occur within this time frame.

- A

DeciderBuilderwill build the configuration for managing exceptions that happened in it’s children. - Whenever a child fails with a

TimeoutExceptionit will restart that child. Restarting creates a new actor instance and the old instance will lose its state. We’ll look at the different strategies in a second. - Whenever another error than

TimeoutExceptionoccurs the actor itself will fail, thus escalating the error.

The parent shouldn’t concern itself with the business logic that happens inside the child. This is exactly why the exceptions hooks don’t hold any reference to the message the caused the child to fail.

We can choose between OneForOneStrategy and a AllForOneStrategy.

The OneForOneStrategy will only focus on the failing actor

in case it fails whilst the AllForOneStrategy will apply the resulting action to all its children.

Next we can choose between four options per kind of exception thrown:

- Restart - creates a new actor instance which can be accessed by the same

ActorRef. By restarting, the state of the previous actor instance was lost (Akka provides a persistence mechanism to prevent this, but we won’t cover it in this post). Notice that it’s mailbox is preserved, but loses the message it was processing. - Stop - Stops the actor instance entirely and doesn’t restart it.

- Resume - the actor reference discards the message it was working on and continuous processing its mailbox. State is preserved because the actor is never destroyed.

- Escalate - The supervisor will fail itself thus escalating the problem to its supervisor.

The strategy object is returned when calling the appropriate method on the SupervisorStrategy which we imported statically.

Besides having to return a method in these hooks we can execute logic,

but keep in mind, we can’t access the failing child’s state or message with which it failed.

Let’s look at some examples where each strategy is suitable.

Example 1: Imagine we have an actor that is responsible for collecting temperature readings from sensors.

This task will delegate getting the measures to child actors, which will call REST endpoints on these sensors.

We choose a OneForOneStrategy because the failing of one sensor doesn’t influence the readings of the other sensors

(the result list of temperature readings been build in the supervisor actor).

Whenever a temperature fails it’s perfectly acceptable to ignore it for the report, thus we choose the stop this service.

Example 2: Imagine an actor that has to sort some objects, it delegates the sorting of 2 objects to child actors.

Whenever a child fails, the result of the supervisor is flawed so it’s better to use a AllForOneStrategy.

Example 3: A child actor that’s task is accessing the database fails

by throwing a TimeoutException, you know that a central discovery service will restart the database shortly.

Now it’s a good time to use the Restart strategy (when you don’t care about its state) or Resume (when you do).

The weather example

Let’s implement this knowledge into the weather example:

private void fetchWeather(FetchTemperatureRequest r) {

// has ~50% change of failing.

long latency = (long) (Math.random() * maxLatency * 2);

Double temperature = Math.random() * maxTemp;

log.info("request {}, started fetching {} temperature", r.requestId, r.type);

if (latency > maxLatency) {

getContext().getSystem().scheduler().scheduleOnce(

FiniteDuration.create(maxLatency, TimeUnit.MILLISECONDS),

getSelf(),

"failover",

getContext().dispatcher(), getSelf()

);

} else {

getContext().getSystem().scheduler().scheduleOnce(

FiniteDuration.create(latency, TimeUnit.MILLISECONDS),

getSender(),

new FetchTemperatureResponse(r.requestId, r.location, r.type, temperature),

getContext().dispatcher(), getSelf()

);

}

getContext().stop(getSelf());

}

Let’s edit the code of the fetchWeather() method.

We create a random time between zero and two times the timeout for the request.

We then schedule either a normal temperature response or a “failover” request.

This request is send to itself, in which case it will throw a TimeoutException.

@Override

public Receive createReceive() {

return receiveBuilder()

.match(FetchTemperatureRequest.class, this::fetchWeather)

.matchEquals("failover",

e -> {

throw new TimeoutException("Waited to long!");

})

.build();

}

Each time we call the REST service it has a 50% fail change. When running the program a few times with logs configured to show actor lifecycle events in the log2, we can discover the standard strategy used by Akka.

The default behavior is to restart actors.

When the strategy is never configured, as is the case here, the actor will be restarted but no new message will be present.

Each actor defines the OneForOneStrategy, this can be seen when either the actual or the predicted actor fails,

only the lifecycle hooks of the failing actor are called.

These hooks also make it apparent that restart is the default. In this case the actors are restarted.

The default behavior of these actors isn’t suitable for our example, so let’s change it.

First we need to think about the actor that needs to handle the TimeoutException.

We might think the PredictionCompareTask is a logical choice, but this wouldn’t result in the PredictionCompareTask

failing when the REST calls fail. In order for a PredictionCompareTask to finish successfully it will

have to collect both Rest calls successfully.

This means that we have to escalate the TimeoutException in the PredictionCompareTask and handle it in the WeatherManager:

@Override

public SupervisorStrategy supervisorStrategy() {

return new AllForOneStrategy(10, Duration.create(1, TimeUnit.MINUTES),

DeciderBuilder

.match(TimeoutException.class, e -> escalate())

.matchAny(o -> restart())

.build());

}

We simply check if one of the child actors fails, and escalate when we do.

Notice that if any other exception than TimeoutException occurs we try to restart.

It doesn’t matter if we use the AllForOneStrategy or the OneForOneStrategy because

all child actors will be stopped anyway by the recursive shutdown the WeatherManager instantiates:

@Override

public SupervisorStrategy supervisorStrategy() {

return new OneForOneStrategy(10, Duration.create(1, TimeUnit.MINUTES),

DeciderBuilder

.match(TimeoutException.class, e -> stop())

.matchAny(o -> escalate())

.build());

}

When we run this code until one of the WeatherService actors fails, we are presented with the following logs:

...[weather-manager/task-0] stopping

...[weather-manager/task-0/fetch-predicted] stopping

...[weather-manager/task-0/fetch-actual] stopping

...[weather-manager/task-0/] stopped

The WeatherManager stops the PredictionCompareTask and this results in the recursive shutdown of its children.

When the children are stopped the PredictionCompareTask is stopped as well.

In the current implementation the service will fail silently (apart from the logs).

Let’s implement business logic in the WeatherManager that keep track of it’s running tasks and watches for unexpected stops:

class WeatherManager extends AbstractActor {

// …

private void comparePrediction(ComparePredictionRequest r) {

log.info("forwarding predictionRequest to child: task {}", r.requestId);

ActorRef task = getContext()

.actorOf(PredictionCompareTask.props(r.location), "task-" + r.requestId);

getContext().watch(task); // <- 1

actorLookup.put(r.requestId, task);

task.tell(r, getSelf());

}

// …

private void handleResponse(ComparePredictionResponse r) {

actorLookup.values().remove(getSender()); // <- 2

getContext().unwatch(getSender()); // <- 2

log.info("Finished request {} :: temp in {} were predicted as {} and was {}"

, r.requestId, r.location, r.report.get("predicted"), r.report.get("actual"));

}

// …

private void terminated(Terminated t) {

ActorRef terminatedActor = t.getActor();

log.error("Task failed"); // <- 3

actorLookup.values().remove(terminatedActor); // <- 3

}

// …

@Override

public Receive createReceive() {

return receiveBuilder()

.match(ComparePredictionRequest.class,

this::comparePrediction)

.match(ComparePredictionResponse.class, this::handleResponse)

.match(Terminated.class, this::terminated) // <- 4

.build();

}

- By watching a task when created, we receive a terminated message whenever the actor stops.

- When a prediction is returned successfully: we don’t care if the actor stops.

It’s not the responsibility of the

WeatherManagerto stop it’s sub tasks. - When we receive a terminated message we will log this as error. We also remove it as a running task.

- When registering actors to watch with

getContext().watch()we receive regularTerminatedmessages.

By storing more information about current running tasks, supervisors can be more verbose about failing tasks

but we didn’t bother for simplicity. Notice that we use this Terminated approach when we want to track which actor failed.

If we don’t care about the specific actor, the SupervisorStrategy also provides hooks for our logic.

Conclusion

By thinking about supervision strategies in our actors, we can configure the system in such a way that failing tasks could be sensibly retried and errors are handled at the right level. Failing components don’t crash the entire system (in most cases) and only corrupted data will be reprocessed. The actor system pushes the developer to decouple their entities.

In the next article we’ll discuss Reactive streams, another method for abstracting asynchronous tasks.

About the author

My name is Thomas Kleinendorst. I'm currently doing my internship at Bottomline where I'm investigating Reactive technologies and how they fit in their new architecture.